ARTICLE

Becoming a media ambassador

Amanda Nicholson

Wildlife Center of Virginia, Waynesboro, VA, USA

Abstract

Speaking with the media is something that many wildlife rehabilitators and educators are faced with at some point in their career, but it makes many people uncomfortable—or maybe even downright terrified! The key to a good media interview is preparation and practice; the goal of this article is to give wildlife professionals some practical, attainable goals while practicing the skill of the interview.

BIO

Amanda Nicholson is the Senior vice president for Outreach and Education of Outreach at the Wildlife Center of Virginia. Amanda oversees the department responsible for public education and community involvement. Amanda supervises the Center’s ever-changing website, manages the “Critter Cams” and moderated discussion, organizes the annual Call of the Wild conference and acts as the associate producer for the Center’s television series, Untamed. She also serves as the program coordinator for the National Wildlife Rehabilitation Association’s annual symposium.

Keywords

Media; interviews; reporters; press; outreach

Citation: Wildlife Rehabilitation Bulletin 2022, 39(1), 31–35, http://dx.doi.org/10.53607/wrb.v39.247

Copyright: Wildlife Rehabilitation Bulletin 2022. © 2022 A. Nicholson. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Accepted: 15 April 2021; Published: 31 May 2022

Correspondence to: Amanda Nicholson, Wildlife Center of Virginia, Waynesboro, VA, USA. E-mail: anicholson@wildlifecenter.org

Introduction

Wildlife rehabilitators and educators have great stories to share; after all, the public loves hearing about wildlife. Given the appealing subject matter, reporters at a variety of media outlets are drawn to wildlife rehabilitators to help share stories. Common media stories include discussion about a current wildlife issue, seasonal observations of wildlife, a particular wildlife patient that has been rescued (typically with human-interest rescue story) or an upcoming event that a wildlife rehabilitator or facility is hosting. As technology allows reporters to be creative and create more stories over greater distances, a media interview may not look like it once did; while reporters still often travel to their interviewee’s location, there are also a growing number of “distance interviews,” utilizing Skype and shared video.

Technology and affordable equipment have also driven amateur media storytelling; more rehabilitation facilities are creating their own “in-house” videos for the public with the help of staff members, volunteers and/or students who have an interest and a knack for minor video filming and editing. These types of projects may feature the work of a wildlife rehabilitator, include staff interviews or perhaps highlight particular skills or techniques for training volunteers and students.

No matter who is on the other end of the camera, it is important that everyone gets the most out of their interview to best display the professional nature of the wildlife rehabilitation and medicine field. A rehabilitator’s time on camera can be extremely valuable—though a terrifying prospect for some, it is an excellent way to represent an organization and/or profession and is a valuable tool to share critical wildlife information with the public. After all, it is a wildlife rehabilitator’s duty to “encourage community support and involvement through … public education” [NWRA 2021].

Before the interview

The best way to avoid panic at the thought of an interview is to take time to prepare. Typically, a reporter will call and set up a time for an interview; many are operating on a tight timeline, but it is common to have at least an hour or two to prepare (if not more). Depending on the story angle, preparation includes re-reading a particular patient’s record, reviewing the natural history of a particular species of wildlife or running through the logistics and timeline of an event. Pick the three most important points that the public should know about the subject matter—the three main takeaways from this information. Sometimes a quick discussion with a co-worker or colleague can be reassuring just to have another knowledgeable person offer feedback or additional thoughts on the topic.

Before the reporter arrives, take a few minutes change into a clean, professional shirt for the interview. Appearance counts and will help shape the way the public views the story and subject.

Staging the interview

Reporters may be coming with an idea for a story, but they might not necessarily understand the greater context of what a wildlife rehabilitator or rehabilitation facility does. A quick tour will help provide the reporter with more context and may help frame the story. On the tour, the interviewee can point out one or two suggested spots for filming the interview. It is usually best to have one or two “pre-approved” places picked out to steer the reporter to a safe, comfortable location; given free choice, reporters may want to film inside a patient enclosure, for example, which would not be appropriate or safe.

Reporters often want their own footage of the animal or particular species in question, but it is important to remember permit conditions, which stipulate that patients may not be shown to the public. If a reporter is able to come and quietly film (without speaking) during a planned procedure, they may be able to get the footage they want for the packaged media story. Otherwise, it will be most helpful for wildlife rehabilitators to supply the reporter with a few short, horizontal video clips and/or photos of the animal or species in the story. It is important to be firm on this point—patient care may not be compromised for the sake of a story. While reporters may desire their own footage, it is not critical that it be their own to create a good story, and wildlife rehabilitators should remain advocates for their patients and profession. It is often helpful to set this expectation ahead of time, to pre-empt additional questions or discussion during the interview.

During the interview: speaking professionally

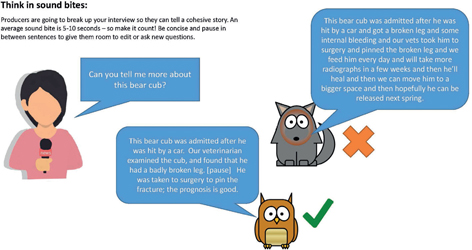

As the interview starts, reflect on the three most important points that viewers should come away with after seeing/hearing this story. Share those point in sound bites—short sentences of about 5–10 s in length. It is important to remember that to create a cohesive story, producers will break up an interview into short snippets; long awkward sentences typically make editing challenging and may be cut out altogether. Pausing briefly in between main points and sentences will allow for easier editing and will keep those important points in the story (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Think in sound bites to provide short concise statements.

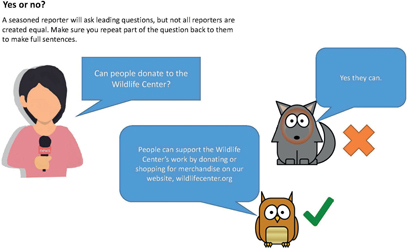

Seasoned reporters typically ask leading questions that will prompt the interviewee to make a full statement, but not all reporters are created equally and some will ask yes or no questions. Never answer “yes” or “no,” this type of answer does not work from a storytelling perspective. Simply remember to repackage the answer with a part of their question to make a complete sentence (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 Always answer in full, complete sentences – even if you are asked a yes or no question.

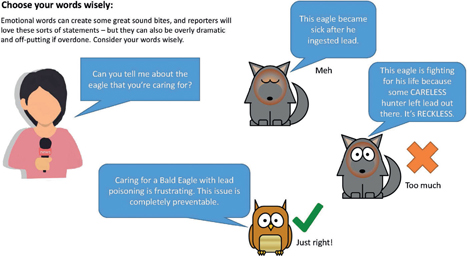

Use bold action words if warranted, but exercise caution and do not overstate the point. Reporters may be drawn to more emotional, dramatic storytelling but always remember to provide professional messaging to the public. Avoid any “off the record” statements; expect that anything said to a reporter may end up in the story in some capacity, since reporters will sometimes use off-camera statements to help shape their story (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Avoid overly dramatic and emotional statements – these may be taken out of context as sound bites!

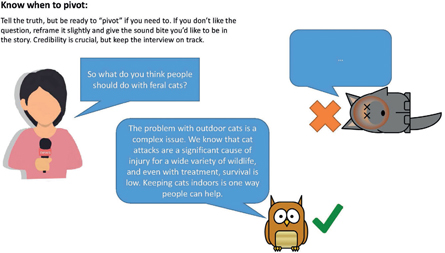

Always tell the truth but be ready to “pivot” if needed. Sometimes reporters may ask questions about large-scale issues that are simply too complicated to cover in a 2-min news story; if the question seems as though it will lead to a difficult discussion, simply reframe the question slightly and give the sound bite that would be most appropriate for the story. Credibility is crucial, but always keep the interview on track and headed in the right direction (Figure 4).

Fig. 4 If you don’t want to answer the specific question you were asked, pause and re-frame the question.

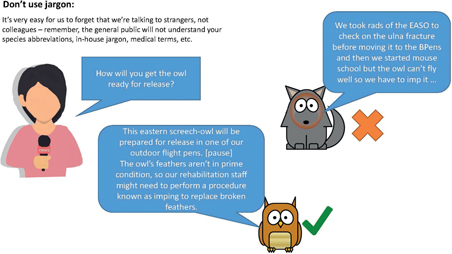

Avoid using jargon; those in the wildlife rehabilitation and medicine field sometimes forget their audience and may use their own terms for species abbreviations (e.g., “EASOs” and “BADOs”), techniques (e.g., “QID feedings” and “auto-squirreling”) and locations (e.g., “B-pens” and “Hold”), which does not make any sense to the general public (Figure 5).

Fig. 5 Remember your audience and avoid using jargon and other “insider” language.

Interviewees should also remember to be aware of personal mannerisms and habits while speaking during the interview. For the most part, those being interviewed can act natural but should avoid a lot of excessive, overt gesturing and nodding. Some mannerisms do not necessarily translate well on camera, but interviewees should also take care not to be completely wooden statues during the interview.

Nearly, all reporters will close the interview with a final question: “anything else?” While those who have not enjoyed the on-camera experience may be tempted to end the interview and be done, this is a final opportunity to include any piece of information in the story that was not already asked. Even if the final answer is something along the lines of “For more information, visit [website],” this can be a good addition to the story (Figure 6).

Fig. 6 Always leave the reporter with a brief summary or takeaway.

After the interview

As the reporter is putting the camera away, ask when the story will air. Media stories are excellent ways to interact with a news outlet via social media and should be shared with supporters. Unless the reporter was truly terrible to work with, tell them how to get in touch about other story ideas; encourage them to follow the organization’s social media presence and website if this is a good way to get ideas for future story.

While many people do not enjoy watching themselves on camera, reviewing the interview is extremely helpful. Interviewees will have a great example of how a media story is assembled and will better understand what sorts of statements work and which ones do not. When a friend or neighbour mentions seeing the story on television, ask what they remember about the interview and what they took away from it. This can be a useful way to gain insight into how the general message was perceived.

The role of B-roll

B-roll is known as the supplemental footage that helps add depth and context to the main interview footage. This footage is incredibly important—even if it is not the main interview, it makes stories much more interesting and captivating. For a wildlife rehabilitator or educator, b-roll may be as simple as quietly working in the background while a colleague is being interviewed or when a cameraperson requests to have a rehabilitator complete a simple task on camera.

Appearing in b-roll is simple; those on camera should just carry on with work as usual. Additional tips include not looking directly into the camera, and taking extra care to make sure appearance is professional.

Audio is not typically used in b-roll, but it is still advisable to curb all extraneous chatter that is not pertinent to the action that is taking place. Additionally, it is often a pet peeve of camera people when those being filmed ask, “Are you filming?” Anyone with a camera pointed at them can just safely assume they are being filmed!

Conclusion

Media stories are wonderful opportunities to share important and educational messages with the public and supporters. Taking time to prepare and present ideas and thoughts professionally can help share powerful and effective messages on behalf of wildlife.

Reference

NWRAwildlife.org. c2021. St. Cloud, MN: National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association. c2021. Accessed on the internet at http://www.nwrawildlife.org on June 2019